PROTOTYPES

PROTOTYPESThe Honda CX500 and Variants

If Google brought you here because you are looking for information on the Honda CX500, GL500, CX650 or GL650, this is just my 'History' page.

My 'main' CX500 Web Resource is here.

Good and Bad Points : Buying Tips

Some folks call them the ugliest bike ever made, and say the "Plastic Maggot" was awful.

These people have never understood the CX500 and have probably never ridden one. Any modern motorcyclist used to plastic-fantastic street racers won't give a CX a second glance. But I say that my CX500 will still be turning heads when the last of today's plastic-fantastics has gone to the scrapyard after 20,000 miles of throttle-bending. My main CX has done 72,000 miles, is 35 years old and still has another 20 years and 38,000 miles left in it. I can give modern 500s a run for their money, and anyway I'll sail past them when they stop for fuel / tighten and lube their chains / cool down. It will probably see me past the age where I can ride it.

CX - Charisma eXtrordinaire

PROTOTYPES

PROTOTYPES

Honda developed the CX500 from two prototype models. Here the CX350 is shown in development form, with the engine married into a modified CB200 frame.

There is not much of the CX500 to see here, and the long exhaust pipes suggest some trouble in Honda's attempts to get the exhaust system right!

However,

the engine does demonstrate one or two of the characteristics of its eventual

grandson.

However,

the engine does demonstrate one or two of the characteristics of its eventual

grandson.

Nobody

seems to know if the CX360 (right) was a production model or an advanced prototype.

Nobody

seems to know if the CX360 (right) was a production model or an advanced prototype.

Here you can see a lot more of the family line; water cooling, engine shape, styling and early Comstar type wheels.

Honda haven't yet effected the twisted cylinder heads of the true CX500.

When

the "real" CX500 arrived in the UK in June 1978 as an in-line-crankshaft

short-stroke V-Twin cylinder, 5 speed, shaft drive, watercooled touring machine

with a capacity of 496cc developing 50 brake horsepower, it was a revelation.

When

the "real" CX500 arrived in the UK in June 1978 as an in-line-crankshaft

short-stroke V-Twin cylinder, 5 speed, shaft drive, watercooled touring machine

with a capacity of 496cc developing 50 brake horsepower, it was a revelation.

Concerned about carburettors and riders' knees colliding, Honda had now twisted the cylinder heads inwards by 22 degrees, giving the engine a very distinctive inlet-exhaust line. The 80-degree firing angle gives the CX that characteristic engine purr, so beloved of V-twin engine fans.

Unusually for Honda engines of the day, it had an overhead valve (OHV, or pushrod-operated) 4-valve-per-cylinder engine. It proved very easy to ride, economical, reliable and unburstable, quickly acquiring a very large following, particularly in the despatch rider market. With the engine placed at the bike's exact centre of gravity, it was surprisingly agile for its size.

Tony says "I just read your review of the CX. I don't know if June was the official launch, but I bought mine from Birmingham M/C at the end of February 1978. I kept it for 3 yrs as a solo before converting it into a trike, using a Triumph Spitfire GT6 rear end. 3 years later it went to a new home somewhere in Notts and I've not seen it since."

The

Moto-Guzzi V50 (right) was the CX's only class rival. It too was an in-line-crankshaft

V-twin, 500cc shaft drive. Its aircooled engine was more bulbous, and although

its Italian styling was more aesthetic than the CX, its performance was inferior,

as was its longevity and general build quality.

The

Moto-Guzzi V50 (right) was the CX's only class rival. It too was an in-line-crankshaft

V-twin, 500cc shaft drive. Its aircooled engine was more bulbous, and although

its Italian styling was more aesthetic than the CX, its performance was inferior,

as was its longevity and general build quality.

The CX500 generally replaced the CB500/4 and CB550/4, the very British-styled CB500T, and arguably the CB400 Superdream, although the ubiquitous Superdream in both 250cc and 400cc variants continued to be produced after the CX arrived. It therefore gave many riders the experience of a "real bike" after passing their UK L-Tests (later, the Part 2 Test), on a 125cc.

Not only is it easy to ride; stable and forgiving, but It was, and is, easy to maintain even for the home mechanic, everything being made simple by the engine layout. With the cylinder heads projecting towards the rider's knees making tappet checks and adjustments is particularly easy, and a decoke is far less hassle than a conventional engine. Honda made the gearbox spin in the opposite direction to the crankshaft, to cancel out most of the torque effect inherent with inline crankshaft V-twin engines. Its barrels, however, are integrated into the engine, being cast into the engine centre section and not detachable.

The early model (shown at the top of the page) was known as either the CX500 or CX500Z (Zero) , and models with the frame numbers in the range 2000001-2034366 suffered a shortcoming in the design of the cam chain tensioner. The spring loaded adjusting blade, released manually by a locknut to take up slack and wear in the cam chain, vibrated excessively and in many cases, broke. This left the rider with, at best, a noisy engine and at worst, a wrecked one. This sad deficiency marred the early days of the CX500 but Honda quickly produced a free fix, consisting of a longer supporting plate and a few modifications to the internal mountings. This did involve removing the engine, but dealers carried out this work for free and nowadays seeing one of the old adjusting mechanisms is very rare indeed.

Having

said that, some CX500Zs do still crop up with unmodified parts. Dealers stamped

three dots (left) in the crankcase, close to the engine serial number, to indicate

that these modifications had been carried out. Any surviving engine of this

vintage is unlikely to be still unmodified.

Having

said that, some CX500Zs do still crop up with unmodified parts. Dealers stamped

three dots (left) in the crankcase, close to the engine serial number, to indicate

that these modifications had been carried out. Any surviving engine of this

vintage is unlikely to be still unmodified.

(Thanks to John for the clear photo.)

Once the early cam chain problems were resolved, the CX500 rapidly became the despatch rider's dream bike. You could seriously neglect it, crash it, leave it out in the foulest weather, run it up and down the motorway all day at 80 and it would never let you down. In the 1980s every other motorcycle in London was a DR and every other DR was on a CX500. The bike quickly acquired a reputation as one of Honda's most successful and reliable models. This explains why so many CXs still survive, compared to the almost equally successful 250 and 400 Superdreams. In the UK today it's rare to see a Superdream about (or even more rare to see a 250 or 400 Dream), but CXs pop out of from under the covers quite regularly, especially as the model gradually acquires cult status.

In 1980 the CX500A was released. Changes to it were mainly cosmetic, such as the polished aluminium radiator shrouds rather than the black plastic one-piece surround of the CX500Z model.

But

it was essentially the same, now fitted with the modified cam

chain adjusting components as standard. The B model (right) followed a year

later with more cosmetic changes. The A/Bs have the polished aluminium radiator

shrouds, a flyscreen, lack the black plastic tabs over the spoke/wheel attachments,

and have a rectangular instead of barrel-shaped front brake master cylinder.

The B has black anodised reversed-plate Comstar wheels, whereas the A has plain

silver ones. Also the B has the improved crankcase breather pipe, which comes

from the rear engine casing instead of from the cylinder head, and the B has

a slightly differently shaped rectangular brake cylinder to the A.

But

it was essentially the same, now fitted with the modified cam

chain adjusting components as standard. The B model (right) followed a year

later with more cosmetic changes. The A/Bs have the polished aluminium radiator

shrouds, a flyscreen, lack the black plastic tabs over the spoke/wheel attachments,

and have a rectangular instead of barrel-shaped front brake master cylinder.

The B has black anodised reversed-plate Comstar wheels, whereas the A has plain

silver ones. Also the B has the improved crankcase breather pipe, which comes

from the rear engine casing instead of from the cylinder head, and the B has

a slightly differently shaped rectangular brake cylinder to the A.

Note that the North American variants usually have a single front disc brake, and as a result, they are distinctly underbraked.

The C "Custom" versions (left) satisfies the more laid-back riders.

The C "Custom" versions (left) satisfies the more laid-back riders.

The Silver Wing (GL500, right) is a fully-faired hard-luggage tourer.

There was also a "D" Deluxe variant (left). Thanks to Ariel Pablo Kulas of Buenos Aires for the photo.

The

CX500 (my bike, the 'A' model, right) is ever a practical motorcycle. It's shaft

drive requires virtually no maintenance, and makes rear

wheel removal a five minute, and hands-clean, job. A massive radiator solves

summer overheating problems and keeps the engine at the optimum temperature,

for both economy and longevity.

The

CX500 (my bike, the 'A' model, right) is ever a practical motorcycle. It's shaft

drive requires virtually no maintenance, and makes rear

wheel removal a five minute, and hands-clean, job. A massive radiator solves

summer overheating problems and keeps the engine at the optimum temperature,

for both economy and longevity.

Undeniably a heavy, and with a full fuel load, particularly top-heavy design, it turns in a surprisingly agile performance for an elderly V-Twin, 500cc pushrod engine. It will cruise comfortably at anything between 50 and 80, and whilst clearing the ton means a long straight road and the ghost of a tailwind, it will top 105 mph in a dive.

Some riders have reported 115 mph, but this must be a doubtful claim on the straight and level.

It's clutch is feather-light, but its chief characteristic is an astonishing amount of torque at low revs, reminiscent of a modern diesel engine. It will trundle along happily at well under 30 mph in 5th gear and still pull away cleanly from that speed. Geared to 12 mph / 1,000 revs and redlined at 9,650, the motor always seems unburstable. Hard indeed is the rider who cannot achieve 50 mpg (Imperial gallons, 8 pints/gallon) and many return 55-60 mpg even at 20-25 years old.

In

1983 the Eurosport model (left) had a major facelift with monoshock rear suspension,

transistorised electronc ignition, new style wheels, and air forks. The standard

set of two x single piston caliper front, and rear drum, brake gave way to 2

x twin piston calipers at the front and single at the rear, vacuum fuel tap

and fuel gauge. This model had an automatic cam chain tensioner, too.

In

1983 the Eurosport model (left) had a major facelift with monoshock rear suspension,

transistorised electronc ignition, new style wheels, and air forks. The standard

set of two x single piston caliper front, and rear drum, brake gave way to 2

x twin piston calipers at the front and single at the rear, vacuum fuel tap

and fuel gauge. This model had an automatic cam chain tensioner, too.

(Thanks to Gaz for the photo. He says he has now removed the ugly rear carrier, and fitted a more aesthetic one!)

Evidently pleased with their success, Honda upped the capacity, and the CX650 (right) was born. (Thanks to Pete MJ for the photo.) Never made in the same numbers, the 650 is an outstandingly good motorcycle, now much sought after by CX fans. Its 673cc capacity overcomes its weight and it's altogether the bike that the 500 should have been.

GL650

(left) came in various guises of different styling, with deluxe hard luggage

and so on. These were particularly popular in the North American market, and

are excellent touring machines.

GL650

(left) came in various guises of different styling, with deluxe hard luggage

and so on. These were particularly popular in the North American market, and

are excellent touring machines.

I can't for the life of me understand why Honda didn't produce this model in 750 or 850 versions, although various other countries had different variants - France's CX400 and Australia's GL700 to name only two. My email correspondence shows that a GL400 recently cropped up in Argentina, and a CX400 in the Netherlands.

Kathy Leslie in Australia says of the GL700 : "The GL700 Wing Interstate model was a production run of about 800 bikes that were made exclusively for the Japanese domestic market during 1983/4. They were meant to satisfy the desire of Japanese motorcyclists to own the GL1100 and GL1200 Goldwings (they weren't allowed to due to a 750cc restriction which has subsequently been removed); and the motor in the GL700 is the same 673cc motor used in all the CX650 models - I guess that in the 'more is better' stakes, 700 is obviously much closer to the 750 limit than 650!!"

Ron

Jesberg sent me this photo of his US Custom 650. A few of these reached the

UK, but they are rarely seen. The styling is quite different to the standard

CXs. Note the single front disc, star wheels, truncated silencers and exaggerated

custom styling. Quite a sought after variant.

Ron

Jesberg sent me this photo of his US Custom 650. A few of these reached the

UK, but they are rarely seen. The styling is quite different to the standard

CXs. Note the single front disc, star wheels, truncated silencers and exaggerated

custom styling. Quite a sought after variant.

Both

the CX500 and CX650 also had Turbo models (CX650T, left) - these are very rare

indeed. I rode the CX650T round Donington once, and it was easily the best bike

I've even been on. Only about 1,700 CX650Ts were made.

Both

the CX500 and CX650 also had Turbo models (CX650T, left) - these are very rare

indeed. I rode the CX650T round Donington once, and it was easily the best bike

I've even been on. Only about 1,700 CX650Ts were made.

Anyone lucky enough to have the chance to ride a 500 or 650 Turbo will wonder where Honda managed to hide the extra engine that seems to be lurking inside the plumbing! The power delivery is very progressive, with a very distinct between-the-ankles rumble as the Turbo starts its business, at which point the extra engine wakes up.

Today the CX500, CX650 and the touring GL models are owned by people more as collector's items than everyday hacks. As time goes by, we hear of CXs being re-discovered in barns, sheds and under tarpaulins in a back garden, having a battery connected and still coming to life (after some persuasion).

These models are now acquiring classic status, and many are being restored to showroom condition. I believe that the model will become as famous as the Triumph Bonneville or the Norton Commando.

The

most reliable part of the bike is undoubtedly its engine. Properly serviced

with oil and filter changes done

on time, the engines just don't go wrong. It's common to look inside a CX motor

after 40,000 miles and find no abnormal wear at all. True, the cam chain and

tensioner will need replacing, and a good mechanic would change

the mechanical water pump seal at the same time, but that's par for the

course at that mileage. The cooling system and electrics are also reliable,

with a couple of cautions which are identified on the Good

& Bad Points page.

The

most reliable part of the bike is undoubtedly its engine. Properly serviced

with oil and filter changes done

on time, the engines just don't go wrong. It's common to look inside a CX motor

after 40,000 miles and find no abnormal wear at all. True, the cam chain and

tensioner will need replacing, and a good mechanic would change

the mechanical water pump seal at the same time, but that's par for the

course at that mileage. The cooling system and electrics are also reliable,

with a couple of cautions which are identified on the Good

& Bad Points page.

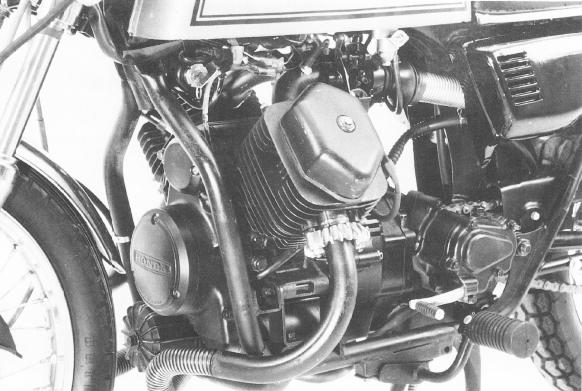

Engine

(left) removed as a complete unit, with radiator, engine hanger and carburettors.

A CX500, CX500A or CX500B, Eurosport, or a GL variant, will fetch anything between £100 for a basket case (the parts alone are worth more than this) and £1,000, even £2,500 for one in really top class condition, especially if it can be proven that maintenance has been correctly done. Typical Ebay price for one in average condition would be £500-£900.

I find that both the CX500s I've owned (FET800V and LUD297W) fitted me like a glove, like a second skin, but that's just me and my riding style. I find it quite manoeuvrable enough and with some practice you can do stall turns (a stall turn is used when filtering though lanes of stationary traffic; without touching down your feet, come to a stop between two lanes, turn 90 degrees left or right, pass between two vehicles, turn 90 degrees again and carry on filtering. Done slickly, it's a very pretty thing to watch).

On fast bends some countersteer is advisable. You don't need fistfuls of countersteer, just a subtle pull. (Countersteer is used on heavy bikes to assist cornering, and you apply backwards pressure on the handlebar on the outside of the turn. Be careful when you try this - it really is a subtle technique.)

The worst technical failure I have had with a CX500 was a blown main fuse. I've done preventative maintenance like mechanical seals, but I've never had a CX blow up or suffer a major failure. Those who have suffered engine failure can usually trace this back to neglect on the part of a previous owner - usually the failure to change the cam chain apparatus at the correct intervals.

The

model is now old enough for some owners to have effected changes to the design.

Andrew Parry's CX (left) shows a solo seat, custom-made side panels and other

cosmetic changes to a "B" engine with "A" wheels.

The

model is now old enough for some owners to have effected changes to the design.

Andrew Parry's CX (left) shows a solo seat, custom-made side panels and other

cosmetic changes to a "B" engine with "A" wheels.

He says that "The bike had been rebuilt,on a Q reg, it has a new frame, different front fairing, single seat, bullet indicators, different mudguards and home made side panels. It does look different from the original, but the mechanics are CX through and through."

This

is a GL250 - the right hand piston, connecting rod and cylinder head have been

removed and a blanking plate fitted. Thanks to Dick (in Raleigh) for permission

to use the photo. He says "The bike pictured is a GL250 Single. The

engine is running in the picture. The frame is my (original owner) 1981 GL500I

with 6,300 miles. The correct engine is out of the frame for a water pump rebuild.

Used the frame to test my single cylinder engine. It actually runs decent. Not

fast but I guarantee you won't complain about the gearing being too low. The

engine is made up from bad and excess parts that were laying around.

This

is a GL250 - the right hand piston, connecting rod and cylinder head have been

removed and a blanking plate fitted. Thanks to Dick (in Raleigh) for permission

to use the photo. He says "The bike pictured is a GL250 Single. The

engine is running in the picture. The frame is my (original owner) 1981 GL500I

with 6,300 miles. The correct engine is out of the frame for a water pump rebuild.

Used the frame to test my single cylinder engine. It actually runs decent. Not

fast but I guarantee you won't complain about the gearing being too low. The

engine is made up from bad and excess parts that were laying around.

"I had to re-balance the crank. The big end of the rod is there to take up space and block the oil passage. The crank came from an engine that spun its right rod bearing. The block has a nice groove in the right bore. Took a chance on an untested stator and it is good. Exhaust will be stock components but haven't decided to use 1/2 of a collector or a piece of pipe. Have to block off 1 passage to the air box hose."

Gasp !!

Here

is the best snap so far of my rebuilt 'Hannover Express' which arrived from

Hannover, Germany in the UK in January 2004 as a pile of bits in the back of

a van.

Here

is the best snap so far of my rebuilt 'Hannover Express' which arrived from

Hannover, Germany in the UK in January 2004 as a pile of bits in the back of

a van.

It was completely rebuilt from scratch, with the metals shot blasted and powder coated, the tank and plastics professionally resprayed, and every part either replaced or cleaned and renovated.

This photo was taken on New Year's Eve 2004.

The CX was replaced by the VT500, which despite being very different, somehow managed to inherit a little of the CX's charisma. It's engine and brakes were a pain to work on, though, and it has an annoying clutch clatter at low revs.

Here's what you can do without removing the engine:-

Oil & Filter change / clutch removal / valve clearances (tappets) / manual cam chain adjustment / water pump removal / cylinder head decoke / Radiator removal / fan removal / oil pump removal

You must remove the engine to do these jobs:-

Mechanical water pump seal replacement / cam chain and tensioners change / crankshaft & piston removal / gearbox removal / rebore / stator change / camshaft removal.

The CX500 does not have detachable cylinder barrels; these are integral with and cast into the centre engine section. Unlike most motorcycle engines, reboring a CX is a major operation. However rebores are rarely done and mileages of 100,000 are normal on the original bores.